Class 2A: Introduction to Programming in Python¶

We will begin at 12:00 PM! Until then, feel free to use the chat to socialize, and enjoy the music!

Firas Moosvi

Class Outline:¶

1st hour - Introduction to Python

Announcements (2 mins)

Introduction (3 mins)

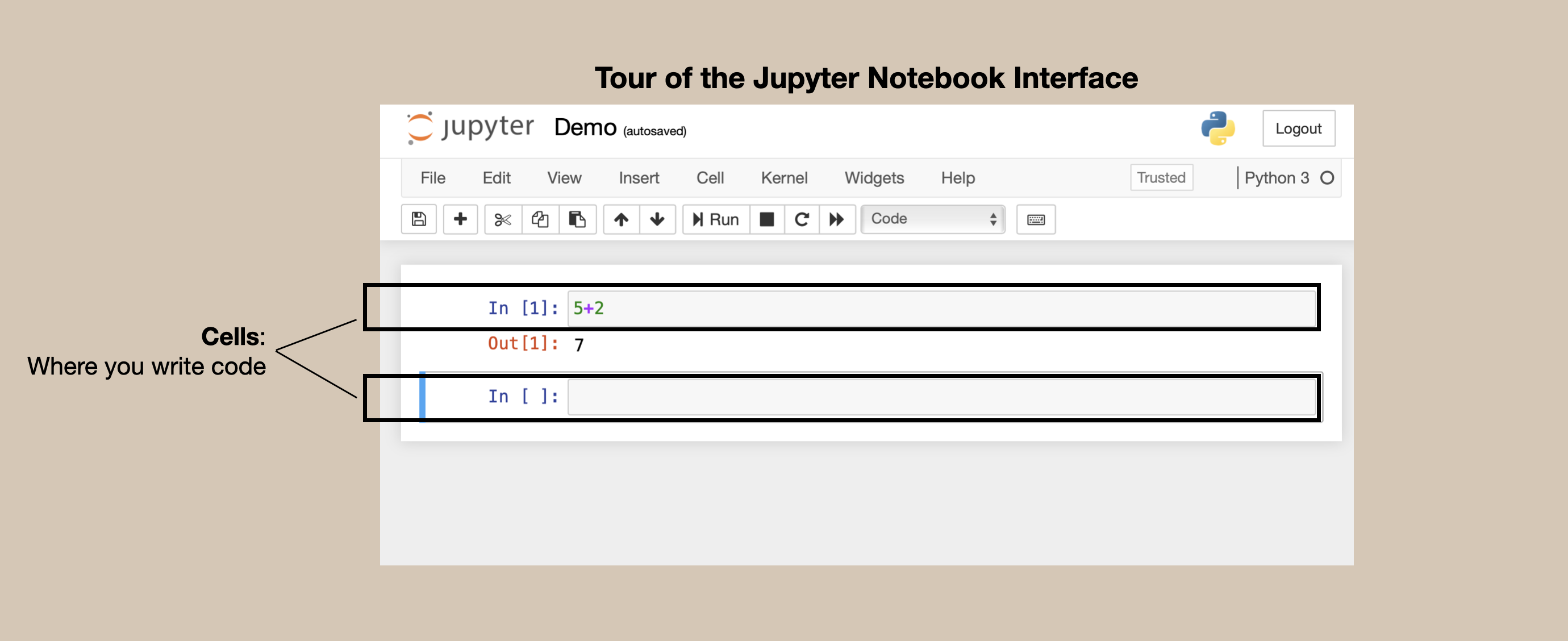

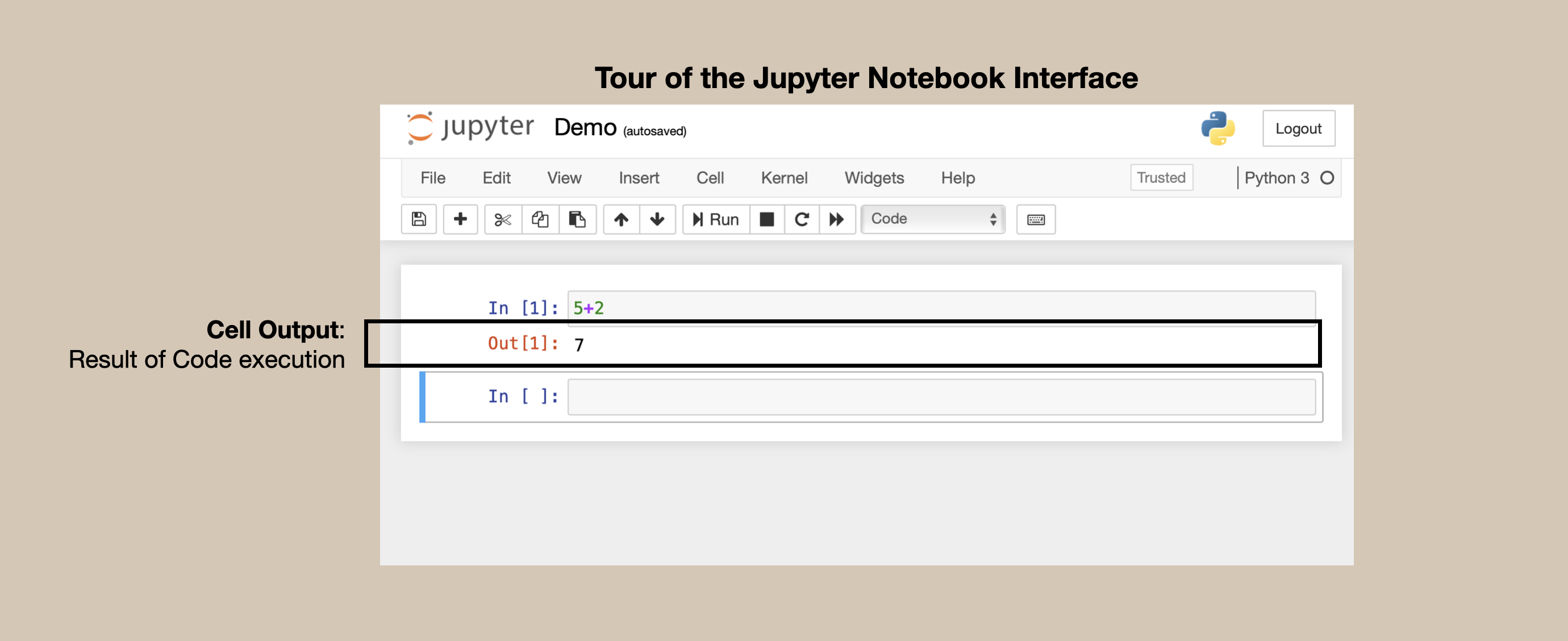

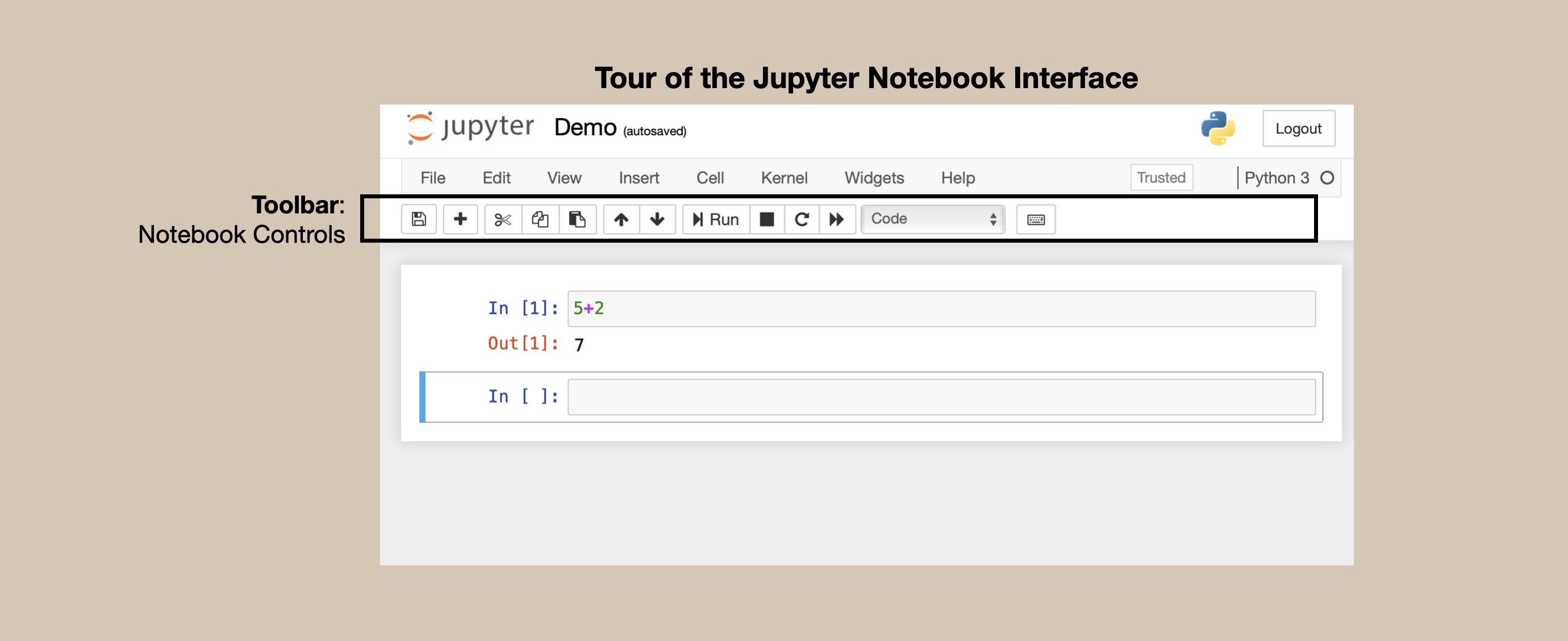

Writing and Running Code (15 min)

Interpreting Code (15 min)

Review and Recap (5 min)

2nd hour - Digging Deeper into Python syntax

Basic datatypes (15 min)

Lists and tuples (15 min)

String methods (5 min)

Dictionaries (10 min)

Conditionals (10 min)

Learning Objectives¶

Become familiar with the course tools and how lectures will be run.

Look at some lines of code and predict what the output will be.

Convert an English sentence into code.

Recognize the order specific lines of code need to be run to get the desired output.

Imagine how programming can be useful to your life!

Part 2: Writing and Running code (15 mins)¶

Using Python to do Math¶

Task |

Symbol |

|---|---|

Addition |

|

Subtraction |

|

Multiplication |

|

Division |

|

Square, cube, … |

|

Squareroot, Cuberoot, … |

|

Trigonometry (sin,cos,tan) |

Later… |

Demo (side-by-side)¶

# Addition

4 + 5 +2

11

# Subtraction

4-5

-1

# Multiplication

4*5

20

# Division

10/2

5.0

# Square, cube, ...

2**3

8

# Squareroot, Cuberoot, ...

4**(1/2)

2.0

Assigning numbers to variables¶

You can assign numbers to a “variable”.

You can think of a variable as a “container” that represents what you assigned to it

There are some rules about “valid” names for variables, we’ll talk about the details later

Rule 1: Can’t start the name of a variable with a number!

General guideline for now: just use a combination of words and numbers

Demo (side-by-side)¶

# Two numbers

num1 = 4000000000000

num2 = 8

print(num1,num2)

4000000000000 8

# Multiply numbers together

num1*num2

32000000000000

Assigning words to variables¶

You can also assign words and sentences to variables!

Surround anything that’s not a number with double quotes ” and “

mysentence = "This is a whole sentence with a list of sports, swimming, tennis, badminton"

print(mysentence)

This is a whole sentence with a list of sports, swimming, tennis, badminton

Using Python to work with words¶

Python has some nifty “functions” to work with words and sentences.

Here’s a table summarizing some interesting ones, we’ll keep adding to this as the term goes on.

Task |

Function |

|---|---|

Make everything upper-case |

|

Make everything lower-case |

|

Capitalize first letter of every word |

|

Count letters or sequences |

|

Demo (side-by-side)¶

mysentence

'This is a whole sentence with a list of sports, swimming, tennis, badminton'

# split on a comma

mysentence.split(',')

['This is a whole sentence with a list of sports',

' swimming',

' tennis',

' badminton']

# make upper case

mysentence.upper()

'THIS IS A WHOLE SENTENCE WITH A LIST OF SPORTS, SWIMMING, TENNIS, BADMINTON'

# make lower case

mysentence.lower()

'this is a whole sentence with a list of sports, swimming, tennis, badminton'

# count the times "i" occurs

mysentence.count('m')

3

# count two characters: hi

mysentence.count('hi')

1

mysentence2 = " Hello. World ..... "

mysentence2

' Hello. World ..... '

mysentence2.strip(' ')

'Hello. World .....'

mysentence2.replace(' ','^')

'^^^^^Hello.^^^^^World^.....^^^^^'

Extending Python¶

Python is a very powerful programming language that allowing you to do a lot out of the box (as you saw!)

We will see lots of examples of interesting things you can do with python

But eventually, you will want to write your own functions to make specific tasks easier

To share code that others have written, they “package” it up and then “import” it so they can use it

Demo (side-by-side)¶

# Numpy is a very popular package to add many more math functions. You can import it like this:

import numpy

# pi

numpy.pi

3.141592653589793

# sin(pi)

numpy.sin(numpy.pi)

1.2246467991473532e-16

# cos(pi)

numpy.cos(numpy.pi)

-1.0

numpy.deg2rad(30)

0.5235987755982988

numpy.pi/6

0.5235987755982988

Activity: Philosophy of Python¶

There are often MANY different ways of doing things; same output, different “code”

There is a philosophy of writing python code, the “pythonic” way of doing things.

Let’s look at this philosophy a bit more carefully.

Demo (side-by-side)¶

import this

The Zen of Python, by Tim Peters

Beautiful is better than ugly.

Explicit is better than implicit.

Simple is better than complex.

Complex is better than complicated.

Flat is better than nested.

Sparse is better than dense.

Readability counts.

Special cases aren't special enough to break the rules.

Although practicality beats purity.

Errors should never pass silently.

Unless explicitly silenced.

In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess.

There should be one-- and preferably only one --obvious way to do it.

Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you're Dutch.

Now is better than never.

Although never is often better than *right* now.

If the implementation is hard to explain, it's a bad idea.

If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea.

Namespaces are one honking great idea -- let's do more of those!

Activity Instructions¶

You will be put into breakout groups of 3-5 people

Introduce yourself! Say Hello, what year you’re in, and what program you’re from

Answer the following questions:

Why do you think these guidelines exist?

Do you think everyone follows these guidelines?

Pick one of the guidelines above and explain what you think it means.

Part 3: Interpreting code (15 mins)¶

Q1: Interpret Code¶

Look at the following code chunk, can you predict what the output will be?

some_numbers = [1, 50, 40, 75, 400, 1000]

for i in some_numbers:

print(i*5)

A. Prints 6 random numbers.

B. Prints the 6 numbers in some_numbers.

C. Prints the 6 numbers in some_numbers multiplied by 5.

D. I don’t know.

# Let's try it!

some_numbers = [1, 50, 40, 75, 400, 1000]

for i in some_numbers:

print(i*5)

5

250

200

375

2000

5000

Q2: Interpret Code¶

Look at the following code chunk, can you predict what the output will be?

some_numbers = [1, 50, 40, 75, 400, 1000]

for i in some_numbers:

if i > 50:

print(i/5)

else:

print(i)

A. Prints the 6 numbers in some_numbers.

B. Prints the number in some_numbers if it is less than 50, otherwise prints the number divided by 5.

C. Prints the number in some_numbers if it is greater than 50, otherwise print the number divided by 5.

D. I don’t know.

# Let's try it!

some_numbers = [1, 50, 40, 75, 400, 1000]

for i in some_numbers:

if i > 50:

print(i/5)

else:

print(i)

1

50

40

15.0

80.0

200.0

Q3: Interpret Code¶

Look at the following code chunk, can you predict what the output will be?

some_numbers = [1, 50, 40, 75, 400, 1000]

def process_number(number):

return (number**2)/10

for i in some_numbers:

if i > 50:

print(process_number(i))

A. Prints the number in some_numbers if it is greater than 50, otherwise prints nothing.

B. Prints the output of the process_number() function applied to some_numbers.

C. Prints the output of the process_number() function if the original number is greater than 50, otherwise prints nothing.

D. I don’t know.

# Let's try it!

some_numbers = [1, 50, 40, 75, 400, 1000]

def process_number(number):

return (number**2)/10

for i in some_numbers:

if i > 50:

print(process_number(i))

562.5

16000.0

100000.0

Q4: Order matters!¶

Suppose you are asked to complete the following operation:

Take the number 5, square it, subtract 2, and then multiply the result by 10

Does the order of the operations you do matter? Yes!

# Let's try it:

((5**2) -2)*10

230

# Here is the same operation as above but in multiple lines```

number = 5

number = number**2

number = number - 2

number = number * 10

print(number)

230

Q5: Parson’s problem¶

A Parson’s Problem is one where you are given all the lines of code to solve the problem, but they are jumbled and it’s up to you to get the right order.

A student would like to get this as the final output of some code that they are writing:

3 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

4 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

5 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

6 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

7 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

8 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

9 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

10 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

11 is bigger than 10!

12 is bigger than 10!

13 is bigger than 10!

14 is bigger than 10!

15 is bigger than 10!

Here are ALL the lines of code they will need to use, but they are scrambled in the wrong order. Can you produce the desired output?

Hint: Pay attention to the indents!

my_numbers = [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]

for i in my_numbers:

if i > 10:

print(i,'is smaller than, or equal to 10.')

else:

print(i,'is bigger than 10!')

my_numbers = [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]

for i in my_numbers:

if i > 10:

print(i,'is bigger than 10!')

else:

print(i,'is smaller than, or equal to 10.')

3 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

4 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

5 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

6 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

7 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

8 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

9 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

10 is smaller than, or equal to 10.

11 is bigger than 10!

12 is bigger than 10!

13 is bigger than 10!

14 is bigger than 10!

15 is bigger than 10!

Congratulations!!¶

You have just shown that you can program!

Over 80% of the course content will be focused on details of the things you’ve seen above:

Numbers and Strings

Loops and Conditionals

Functions

If you followed along with most of what we covered, you’re in good shape for this course

Part 4: Review and Recap (5 mins)¶

Using Python to do Math¶

Task |

Symbol |

|---|---|

Addition |

|

Subtraction |

|

Multiplication |

|

Division |

|

Square, cube, … |

|

Squareroot, Cuberoot, … |

|

Trigonometry (sin,cos,tan) |

|

Using Python to work with words (Strings)¶

Python has some nifty “functions” to work with words and sentences.

Here’s a table summarizing some interesting ones, we’ll keep adding to this as the term goes on.

Task |

Function |

|---|---|

Make everything upper-case |

|

Make everything lower-case |

|

Capitalize first letter of every word |

|

Count letters or sequences |

|

Zen of Python¶

import this produces the pythonic philosophy:

The Zen of Python, by Tim Peters

Beautiful is better than ugly.

Explicit is better than implicit.

Simple is better than complex.

Complex is better than complicated.

Flat is better than nested.

Sparse is better than dense.

Readability counts.

Special cases aren't special enough to break the rules.

Although practicality beats purity.

Errors should never pass silently.

Unless explicitly silenced.

In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess.

There should be one-- and preferably only one --obvious way to do it.

Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you're Dutch.

Now is better than never.

Although never is often better than *right* now.

If the implementation is hard to explain, it's a bad idea.

If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea.

Namespaces are one honking great idea -- let's do more of those!

Learning Objectives¶

Become familiar with the course tools and how lectures will be run.

Describe how to use built-in python functions to do operations on numbers

Describe how to use built-in python functions to do operations on words

Look at some lines of code and predict what the output will be.

Recognize the order specific lines of code need to be run to get the desired output.

Imagine how programming can be useful to your life!

Next Hour¶

We will dive into details on more python syntax to ready ourselves for Data Analysis:

- Lists and Tuples

- String methods

- Dictionaries

- Conditionals

See you after the break!

Break¶

Attribution¶

The original version of these Python lectures were by Patrick Walls.

These lectures were delivered by Mike Gelbart and are available in their original format, publicly here.

In this class, we go through a notebook by a former colleague, Dr. Mike Gelbart, option co-director of the UBC-Vancouver MDS program.

If you prefer, you can also watch his recording of the same material.

Class Outline:¶

Basic datatypes (15 min)

Lists and tuples (15 min)

String methods (5 min)

Dictionaries (10 min)

Conditionals (10 min)

Basic datatypes¶

A value is a piece of data that a computer program works with such as a number or text.

There are different types of values:

42is an integer and"Hello!"is a string.A variable is a name that refers to a value.

In mathematics and statistics, we usually use variables names like \(x\) and \(y\).

In Python, we can use any word as a variable name (as long as it starts with a letter and is not a reserved word in Python such as

for,while,class,lambda,import, etc.).

And we use the assignment operator

=to assign a value to a variable.

See the Python 3 documentation for a summary of the standard built-in Python datatypes. See Think Python (Chapter 2) for a discussion of variables, expressions and statements in Python.

Common built-in Python data types¶

English name |

Type name |

Description |

Example |

|---|---|---|---|

integer |

|

positive/negative whole numbers |

|

floating point number |

|

real number in decimal form |

|

boolean |

|

true or false |

|

string |

|

text |

|

list |

|

a collection of objects - mutable & ordered |

|

tuple |

|

a collection of objects - immutable & ordered |

|

dictionary |

|

mapping of key-value pairs |

|

none |

|

represents no value |

|

Numeric Types¶

x = 42

print(x)

42

type(x)

int

print(x)

42

x # in Jupyter we don't need to explicitly print for the last line of a cell

42

pi = 3.14159

print(pi)

3.14159

type(pi)

float

λ = 2

Arithmetic Operators¶

The syntax for the arithmetic operators are:

Operator |

Description |

|---|---|

|

addition |

|

subtraction |

|

multiplication |

|

division |

|

exponentiation |

|

integer division |

|

modulo |

Let’s apply these operators to numeric types and observe the results.

1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5

15

0.1 + 0.2

0.30000000000000004

Tip

Note From Firas: This is floating point arithmetic. For an explanation of what’s going on, see this tutorial.

2 * 3.14159

6.28318

2**10

1024

type(2**10)

int

2.0**10

1024.0

int_2 = 2

float_2 = 2.0

float_2_again = 2.

101 / 2

50.5

101 // 2 # "integer division" - always rounds down

50

101 % 2 # "101 mod 2", or the remainder when 101 is divided by 2

1

None¶

NoneTypeis its own type in Python.It only has one possible value,

None

x = None

print(x)

None

type(x)

NoneType

You may have seen similar things in other languages, like null in Java, etc.

Strings¶

Text is stored as a type called a string.

We think of a string as a sequence of characters.

We write strings as characters enclosed with either:

single quotes, e.g.,

'Hello'double quotes, e.g.,

"Goodbye"triple single quotes, e.g.,

'''Yesterday'''triple double quotes, e.g.,

"""Tomorrow"""

my_name = "Mike Gelbart"

print(my_name)

Mike Gelbart

type(my_name)

str

course = 'DATA 301'

print(course)

DATA 301

type(course)

str

If the string contains a quotation or apostrophe, we can use double quotes or triple quotes to define the string.

"It's a rainy day cars'."

"It's a rainy day cars'."

sentence = "It's a rainy day."

print(sentence)

It's a rainy day.

type(sentence)

str

saying = '''They say:

"It's a rainy day!"'''

print(saying)

They say:

"It's a rainy day!"

Boolean¶

The Boolean (

bool) type has two values:TrueandFalse.

the_truth = True

print(the_truth)

True

type(the_truth)

bool

lies = False

print(lies)

False

type(lies)

bool

Comparison Operators¶

Compare objects using comparison operators. The result is a Boolean value.

Operator |

Description |

|---|---|

|

is |

|

is |

|

is |

|

is |

|

is |

|

is |

|

is |

2 < 3

True

"Data Science" != "Deep Learning"

True

2 == "2"

False

2 == 2.00000000000000005

True

Operators on Boolean values.

Operator |

Description |

|---|---|

|

are |

|

is at least one of |

|

is |

True and True

True

True and False

False

False or False

False

# True and True

("Python 2" != "Python 3") and (2 <= 3)

True

not True

False

not not not not True

True

Casting¶

Sometimes (but rarely) we need to explicitly cast a value from one type to another.

Python tries to do something reasonable, or throws an error if it has no ideas.

x = int(5.0)

x

5

type(x)

int

x = str(5.0)

x

'5.0'

type(x)

str

str(5.0) == 5.0

False

list(5.0) # there is no reasonable thing to do here

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

/tmp/ipykernel_1778/1323977772.py in <module>

----> 1 list(5.0) # there is no reasonable thing to do here

TypeError: 'float' object is not iterable

int(5.3)

5

Lists and Tuples¶

Lists and tuples allow us to store multiple things (“elements”) in a single object.

The elements are ordered.

my_list = [1, 2, "THREE", 4, 0.5]

print(my_list)

[1, 2, 'THREE', 4, 0.5]

type(my_list)

list

You can get the length of the list with len:

len(my_list)

5

today = (1, 2, "THREE", 4, 0.5)

print(today)

(1, 2, 'THREE', 4, 0.5)

type(today)

tuple

len(today)

5

Indexing and Slicing Sequences¶

We can access values inside a list, tuple, or string using the bracket syntax.

Python uses zero-based indexing, which means the first element of the list is in position 0, not position 1.

Sadly, R uses one-based indexing, so get ready to be confused.

my_list

[1, 2, 'THREE', 4, 0.5]

my_list[0]

1

my_list[4]

0.5

my_list[5]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

IndexError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-199-075ca585e721> in <module>

----> 1 my_list[5]

IndexError: list index out of range

today[4]

We use negative indices to count backwards from the end of the list.

my_list

[1, 2, 'THREE', 4, 0.5]

my_list[-1]

0.5

We use the colon : to access a subsequence. This is called “slicing”.

my_list[1: ]

[2, 'THREE', 4]

Above: note that the start is inclusive and the end is exclusive.

So

my_list[1:3]fetches elements 1 and 2, but not 3.In other words, it gets the 2nd and 3rd elements in the list.

We can omit the start or end:

my_list[0:3]

[1, 2, 'THREE']

my_list[:3]

[1, 2, 'THREE']

my_list[3:]

[4, 0.5]

my_list[:] # *almost* same as my_list - more details next week (we might not, just a convenience thing)

[1, 2, 'THREE', 4, 0.5]

Strings behave the same as lists and tuples when it comes to indexing and slicing.

alphabet = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwyz"

alphabet[0]

'a'

alphabet[-1]

'z'

alphabet[-3]

'w'

alphabet[:5]

'abcde'

alphabet[12:20]

'mnopqrst'

List Methods (Functions)¶

A list is an object and it has methods for interacting with its data.

For example,

list.append(item)appends an item to the end of the list.See the documentation for more list methods.

primes = [2,3,5,7,11]

primes

[2, 3, 5, 7, 11]

len(primes)

5

primes.append(13)

primes

[2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13]

len(primes)

6

max(primes)

13

min(primes)

2

sum(primes)

41

[1,2,3] + ["Hello", 7]

[1, 2, 3, 'Hello', 7]

Sets¶

Another built-in Python data type is the

set, which stores an un-ordered list of unique items.More on sets in DSCI 512.

s = {2,3,5,5,11}

s

{2, 3, 5, 11}

{1,2,3} == {3,2,1}

[1,2,3] == [3,2,1]

s.add(2) # does nothing

s

s[0]

Above: throws an error because elements are not ordered.

Mutable vs. Immutable Types¶

Strings and tuples are immutable types which means they cannot be modified.

Lists are mutable and we can assign new values for its various entries.

This is the main difference between lists and tuples.

names_list = ["Indiana","Fang","Linsey"]

names_list

['Indiana', 'Fang', 'Linsey']

names_list[0] = "Cool guy"

names_list

['Cool guy', 'Fang', 'Linsey']

names_tuple = ("Indiana","Fang","Linsey")

names_tuple

('Indiana', 'Fang', 'Linsey')

names_tuple[0] = "Not cool guy"

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-236-bd6a1b77b220> in <module>

----> 1 names_tuple[0] = "Not cool guy"

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

Same goes for strings. Once defined we cannot modifiy the characters of the string.

my_name = "Mike"

my_name[-1] = 'q'

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-238-94c4564b18e3> in <module>

----> 1 my_name[-1] = 'q'

TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

x = ([1,2,3],5)

x[1] = 7

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-240-415ce6bd0126> in <module>

----> 1 x[1] = 7

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

x

([1, 2, 3], 5)

x[0][1] = 4

x

String Methods¶

There are various useful string methods in Python.

all_caps = "HOW ARE YOU TODAY?"

print(all_caps)

HOW ARE YOU TODAY?

new_str = all_caps.lower()

new_str

'how are you today?'

Note that the method lower doesn’t change the original string but rather returns a new one.

all_caps

'HOW ARE YOU TODAY?'

There are many string methods. Check out the documentation.

all_caps.split()

['HOW', 'ARE', 'YOU', 'TODAY?']

all_caps.count("O")

3

One can explicitly cast a string to a list:

caps_list = list(all_caps)

caps_list

['H',

'O',

'W',

' ',

'A',

'R',

'E',

' ',

'Y',

'O',

'U',

' ',

'T',

'O',

'D',

'A',

'Y',

'?']

len(all_caps)

18

all_caps = all_caps + 'O' + 'o'

all_caps.count('O')

4

len(caps_list)

18

String formatting¶

Python has ways of creating strings by “filling in the blanks” and formatting them nicely.

There are a few ways of doing this. See here and here for some discussion.

Old formatting style (borrowed from the C programming language):

F-Strings (aka magic)¶

New formatting style (see this article):

name = "Sasha"

age = 4

template_new = f"Hello, my name is {name}. I am {age} years old."

template_new

'Hello, my name is Sasha. I am 4 years old.'

Dictionaries¶

A dictionary is a mapping between key-values pairs.

house = {'bedrooms': 3,

'bathrooms': 2,

'city': 'Vancouver',

'price': 2499999,

'date_sold': (1,3,2015)}

condo = {'bedrooms' : 2,

'bathrooms': 1,

'city' : 'Burnaby',

'price' : 699999,

'date_sold': (27,8,2011)

}

We can access a specific field of a dictionary with square brackets:

house['price']

2499999

condo['price']

699999

condo['city']

'Burnaby'

We can also edit dictionaries (they are mutable):

condo['price'] = 5 # price already in the dict

condo

{'bedrooms': 2,

'bathrooms': 1,

'city': 'Burnaby',

'price': 5,

'date_sold': (27, 8, 2011)}

condo['flooring'] = "wood"

condo

{'bedrooms': 2,

'bathrooms': 1,

'city': 'Burnaby',

'price': 5,

'date_sold': (27, 8, 2011),

'flooring': 'wood'}

We can delete fields entirely (though I rarely use this):

del condo["city"]

condo

{'bedrooms': 2,

'bathrooms': 1,

'price': 5,

'date_sold': (27, 8, 2011),

'flooring': 'wood'}

condo[5] = 443345

condo

{'bedrooms': 2,

'bathrooms': 1,

'price': 5,

'date_sold': (27, 8, 2011),

'flooring': 'wood',

5: 443345}

condo[(1,2,3)] = 777

condo

{'bedrooms': 2,

'bathrooms': 1,

'price': 5,

'date_sold': (27, 8, 2011),

'flooring': 'wood',

5: 443345,

(1, 2, 3): 777}

condo["nothere"]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-20-aec15e89a3c8> in <module>

----> 1 condo["nothere"]

KeyError: 'nothere'

A sometimes useful trick about default values:

condo["bedrooms"]

2

is shorthand for

condo.get("bedrooms")

2

With this syntax you can also use default values:

condo.get("bedrooms", "unknown")

2

condo.get("fireplaces", "unknown")

'unknown'

Empties¶

lst = list() # empty list

lst

lst = [] # empty list

lst

tup = tuple() # empty tuple

tup

tup = () # empty tuple

tup

dic = dict() # empty dict

dic

dic = {} # empty dict

dic

st = set() # emtpy set

st

st = {} # NOT an empty set!

type(st)

st = {1}

type(st)

Conditionals¶

Conditional statements allow us to write programs where only certain blocks of code are executed depending on the state of the program.

Let’s look at some examples and take note of the keywords, syntax and indentation.

Check out the Python documentation and Think Python (Chapter 5) for more information about conditional execution.

name = input("What's your name?")

if name.lower() == 'mike':

print("That's my name too!")

elif name.lower() == 'santa':

print("That's a fun name.")

else:

# print("Hello {}! That's a cool name.".format(name))

print(f"Hello {name}! That's a cool name.")

print('Nice to meet you!')

What's your name?Firas

Hello Firas! That's a cool name.

Nice to meet you!

bool(None)

The main points to notice:

Use keywords

if,elifandelseThe colon

:ends each conditional expressionIndentation (by 4 empty space) defines code blocks

In an

ifstatement, the first block whose conditional statement returnsTrueis executed and the program exits theifblockifstatements don’t necessarily needeliforelseeliflets us check several conditionselselets us evaluate a default block if all other conditions areFalsethe end of the entire

ifstatement is where the indentation returns to the same level as the firstifkeyword

If statements can also be nested inside of one another:

name = input("What's your name?")

if name.lower() == 'mike':

print("That's my name too!")

elif name.lower() == 'santa':

print("That's a funny name.")

else:

print("Hello {0}! That's a cool name.".format(name))

if name.lower().startswith("super"):

print("Do you have superpowers?")

print('Nice to meet you!')

Inline if/else¶

words = ["the", "list", "of", "words"]

x = "long list" if len(words) > 10 else "short list"

x

if len(words) > 10:

x = "long list"

else:

x = "short list"

x